Nelson’s Native American stories are an excellent addition to any multicultural lesson. His many historical children’s books include maps, informative timelines, and detailed author’s notes helpful to teachers and parents.

Gift Horse: A Lakota Story

Author’s Note Selection

My great-great grandfather’s name was Maȟpíya Kiny’An, or Flying Cloud, and he was a Lakota Warrior. I am a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in the Dakotas, descendants of the Lakota Indigenous People about whom this story is told. Many times I have wondered what it was like for Flying Cloud, as a boy, growing up. That is how I came to write this tale. When I was a child, my mother, Christine-Elk Tooth Woman, often told me about the Old Ones who came before her, including Flying Cloud.

Lakota Indians are also known as the Sioux. This label, which means “snakes” in the most reviled sense of the word, was originally given to them by their Ojibwa [Anishinaabe/Chippewa] enemies. However, today, Sioux denotes the proud race of the Plains Indians still living in the Dakotas.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Lakota lived on the vast grasslands of what is now the central part of the United States. Mounted on horses, they followed the great herds of buffalo that supplied them with most of their food and clothing, and even skins to cover their tipis. They lived as part of the natural world, integrating themselves into it. For guidance and understanding they called upon Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, who is the life force that exists within all things. The Lakota lived in harmony with the changing seasons, with all of the other creatures, and with all of the different elements in their environment. Their manner of life reflected the lives around them; for instance, they hunted in hands much as wolves do. They revered all of Creation Sun, Moon, Stars, Mother Earth and called the four-legged beings and the winged creatures their brothers. To this day, the Lakota believe that the green growing things are their relatives. A curious contradiction of humanity is that they did not always get along with their neighboring Indian tribes and were known as fierce warriors. In 1876 the Lakota and Cheyenne joined together to defeat General Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Horses were considered a sacred animal, and one of the finest gifts that a person could give to another. The Lakota painted their horses and decorated their own bodies as a symbolic connection to the natural world . . .

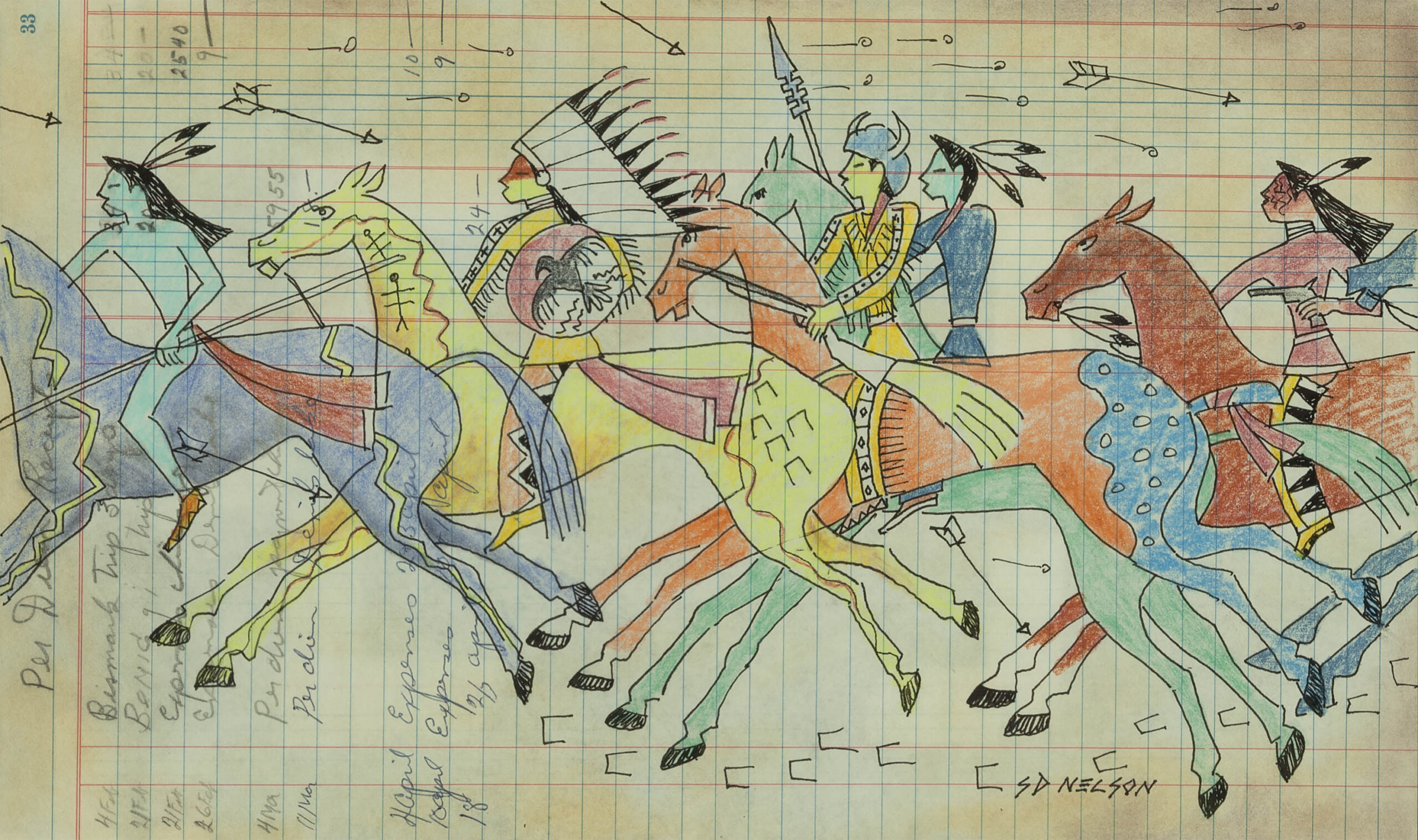

Ledger Art

During the late 1800’s the Indigenous people of the American Great Plains developed a unique art style known as ledger art. Using pens, colored pencils, and watercolors, they made drawings on the ruled-lined paper of discarded accounting books called ledger books. With simple bold shapes and vivid colors, they depicted battles, village scenes, ceremonies, and even their imprisonment. The figures of people, horses and other animals are typically drawn in profile with very simplified features. Their images are laid down directly upon lined pages that are filled with lists of merchandise and accounting numbers.

Art critics, collectors and art historians have great admiration for the traditional and contemporary work of Indigenous ledger artists.

My illustrations offer a contemporary interpretation of traditional ledger-style artwork. Originally, my Lakota people painted on animal skins but, with the coming of the Euro-Americans, their hunting ways drastically ended. They turned to paper to create their art. Living near, or imprisoned in U.S. forts, they were given discarded ledger books filled with lists of merchandise and numbers. The used record books had served the tradesman’s purpose and were headed for the trash heap. Instead, Native men used them as the surface to create images of their vanishing culture. Ironically, and in a visually striking manner, the intentions of the bookkeeper and the Indian artist remain separate—like oil on water. The Indian’s images seem to float atop the ruled-lined paper of the “white man” with its strange written words and numbers. Sadly, and in the most compelling way, the two cultures never seem to connect. In many ways that disconnection continues today.

– SD Nelson